Love Centered Accountability by Dr. Danielle Lee Moss

/Content Notice: The purpose of the #LoveWITHAccountability forum on The Feminist Wire and project is to prioritize child sexual abuse, healing, and justice in national dialogues and work on racial justice and gender-based violence. Several of the featured articles in this forum give an in-depth and, at times, graphic examination of rape, molestation, and other forms of sexual harm against diasporic Black children through the experiences and work of survivors and advocates. The articles also offer visions and strategies for how we can humanely move towards co-creating a world without violence. Please take care of yourself while reading.

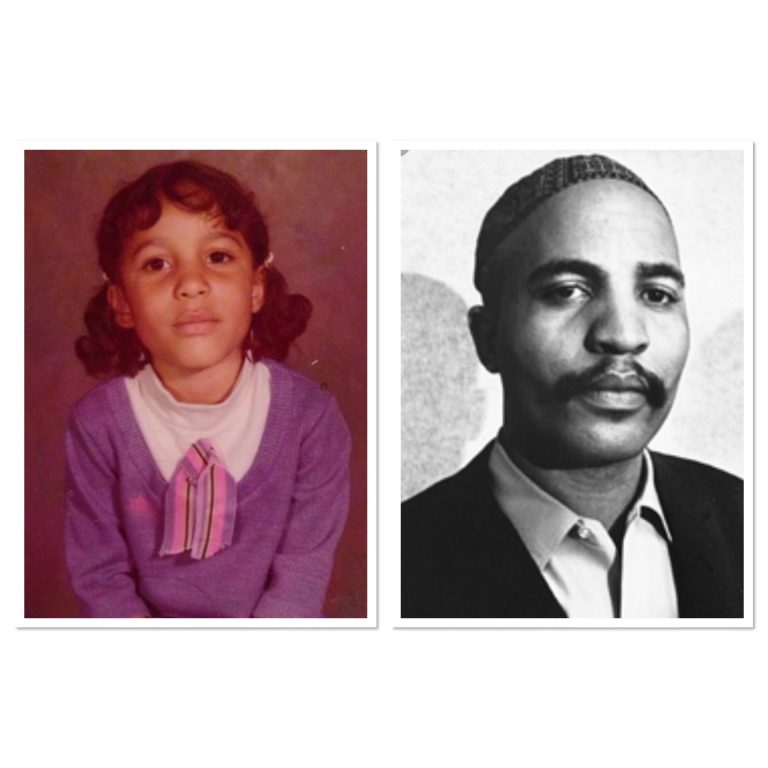

By Dr. Danielle Lee Moss

Childhood sexual abuse. Even for transcendent me, the words sit still and sickening in my throat. Childhood sexual abuse. When I see it written as CSA, my nervous stomach quiets; it gives me the distance I need to tackle the topic. CSA is the dirty secret we gift to our children through our silence, our rage, our shame – over generations. Whether the abusers are family members or authority figures with access to our children, we teach them that sex and feelings and bodies don’t make for polite conversation. We give their genitalia nick names. And, though we have created a sexualized world – a world that has few spaces where children can live free from gender roles, fear, or creeping hands – we remain challenged to speak its existence. Regrettably, our reality is that sometimes, and for the worst reasons, childhood and sex come together. The resulting wounds become permanent because we teach our children that the things that cut into them the most are the things that must not be named, or spoken of, or confronted. In fact, most of childhood pivots around the notion that children are most childlike when they powerless. In fact, the social arrangement relies on children’s ability to “recognize authority”. To date, the United States remains one of only two countries that have failed to ratify the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child.

According to UNICEF, among the tenets of this international treaty is a commitment that countries

[…] “must ensure that all children—without discrimination in any form—benefit from special protection measures and assistance; have access to services such as education and health care; can develop their personalities, abilities and talents to the fullest potential; grow up in an environment of happiness, love and understanding; and are informed about and participate in, achieving their rights in an accessible and active manner.”[…]

So, what does this mean for loved centered accountability? Most of us don’t understand what this means because accountability and discipline usually show up as punishment and pain in our cultural lexicon. How many of us heard parents say they beat us out of love growing up? We condition our kids to a love/pain connection early on. Embarrassment and humiliation are also deeply wedded to notions of love centered accountability. At home, in school, and even via social media, part of the way we illicit children’s cooperation and compliance is by the fear of public shame. The social contract we’ve created with childhood gives way to a legacy of childhood sexual abuse that is seemingly intractable because it exists in a larger anti-child social context. The shame is multigenerational and supersedes our ability to adequately protect our children. Many survivors talk about the added isolation and rejection they experienced as their brave disclosures went unrecognized. The denial and rejection of brave disclosure is rooted in the same concepts of shame and fear. For many, being brought into the circle of brave disclosure is experienced as the transference of shame, and not the illumination of truth. Despite our failure as a society to adequately address CSA as a problem that cuts across race and class, the reality is that even what goes unnoticed, unacknowledged, and unrecognized grows roots that sprout and expand and cripple.

A few years ago, I heard a comedian call out childhood sexual abuse in an arena full of people. He was talking about a public rape case that had taken over several news outlets, and he said, “Some of you defending this dude are still scared to go to the family cookout because you know you’re going to see that molester relative there.” The crowd swayed, laughing/not laughing, in palpable discomfort. The joke, which sat in the arena like stinking fog, suggests that accountability is completely out of the question, that the spiritual imbalance of secrecy and shame are members of the family now – although we know that sexual abuse doesn’t always involve relatives. The social contract for CSA survivors and perpetrators – even when they embody the same beings – is silence and distance. What do you do when the people who hurt you the most are part of the very fabric and foundation of your life? When their stories and joys and tears and faith and misery are entwined in the heartbeat of your life? We don’t understand accountability and love as the same, because we are a crime and punishment society. We define and confine people by their worst actions with no roadmap leading back to restoration and redemption. We are so punitive, in fact, that if the person who finds the cure for cancer kills a puppy in the same week, we might be inclined to reject the cure. The extreme polarity of love and accountability make confession and redemption an unimaginable risk, because in the world we live in repentance can never interrupt the abuser scourged identity.

Living in a punitive, crime and punishment society makes the idea of #LoveWITHAccountability almost inconceivable. What on earth would be unearthed if we began to explore this notion in the context of childhood sexual abuse? What would happen if we said to the people who hurt us, who we still by circumstance had to interact with, that the road to healing was awareness, confession, acknowledgement, and restitution? Luckily, everything we live we have created. We are more than capable of creating something different, something courageous. We can tackle our private spaces on this issue in ways that lead to recovery and restoration. This requires brave disclosure, highly visible efforts to right wrongs, and a release from shame. We also have the opportunity to engage in broader, public conversations that allow survivors and abusers and those indirectly effected by CSA to engage in dialogue without the vulnerability and judgement that can come with brave disclosure. Creating a shame free discourse on childhood and power, sexuality, and sexual identity, and bodies and consent is central to clearly the way for #LoveWITHAccountability.

Accountability is the way to loving ourselves and being in meaningful relationship and connection with others. Love is free, but it is not solitary. Love is a binding agreement whose essence is respect, consideration, benevolence, kindness, accountability, and authenticity. Survivors, or transcenders, must first extend this love to themselves. You can’t call on anyone to acknowledge your light until you know what it feels like to be loved by you, to see your own light reflected back at you and to be warmed by its brilliance. Love makes space for truth, and truth is the only way to restorative reconciliation. This is particularly important in cases when abusers and survivors continue to be in relationship. Restorative reconciliation says,

“You did this to me, you are sorry, and neither of us has to be defined by the worst thing you ever did.”

Truth makes forgiveness, even when it is not requested, possible. Because love knows that truth is sometimes a one-sided conversation. It means that transcenders must love themselves unconditionally, courageously, and completely because of who they are, and not because of or in spite of what they’ve been through.

Dr. Danielle Moss Lee is President and CEO of the YWCA of the City of New York. She was appointed by Mayor DeBlasio to New York City’s Commission on Gender Equity, is Co-Chair of the NY City Council’s Young Women’s Initiative, and President of Black Agency Executives. Her contributions to education and the social sector have been recognized by the New York State Education Department and The New York City Comptroller’s Office, among others. In 2015 The Network Journal named her one of the 25 Most Influential Black Women in Business. Dr. Moss Lee has contributed to The Daily Beast, The Huffington Post, Edutopia, The Amsterdam News, and City Limits Magazine. She holds M.A. and Ed.M. degrees from Teachers College Columbia University, where she also completed her Doctorate in Organization and Leadership with a focus on Education Administration. She received her B.A. from Swarthmore College with a degree in both English Literature and History with a concentration in Black Studies.