Soul Survivor: Reimagining Legacy by Chevara Orrin

/Content Notice: The purpose of the #LoveWITHAccountability forum on The Feminist Wire and project is to prioritize child sexual abuse, healing, and justice in national dialogues and work on racial justice and gender-based violence. Several of the featured articles in this forum give an in-depth and, at times, graphic examination of rape, molestation, and other forms of sexual harm against diasporic Black children through the experiences and work of survivors and advocates. The articles also offer visions and strategies for how we can humanely move towards co-creating a world without violence. Please take care of yourself while reading.

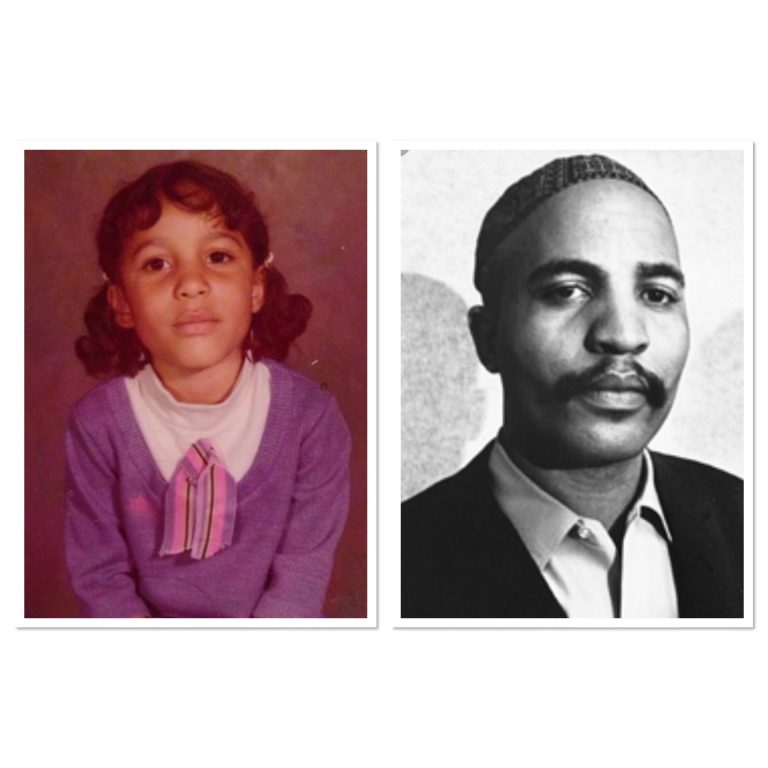

By Chevara Orrin

I once believed, as I told a reporter,

“He altered my life. Whoever I was to become: I am someone else.”

I now know I am exactly who I was meant to be. In spite of, and because of, my father.

Forgiveness is at the core of the personal work I’ve done for several decades trying to reconcile within my own heart and life my father’s “legacy” and his horrific violations against my sisters and me.

I know well the burden of secrecy, the complexity of family, and the difficulty of speaking truth.

I am a survivor of incest. I am a survivor of sexual and domestic violence. I am a survivor of brutality perpetrated at the hands of Black men. I am also the mother of Black sons. I understand the complexity and challenge of simultaneously being charged with protecting our community and holding our community accountable. For most of my life, I’ve struggled with reconciling my father’s abuse of my body, rape of my soul, destruction of my spirit AND honoring his incredible legacy of social justice and civil rights. I believe there is space for both. One of my sisters reminded us often during our father’s 2008 incest trial,

“We are all better than the worst things we’ve ever done.”

I believe that. I do not believe there is ever any excuse for sexual violence or abuse. This is my truth.

Forgiveness and reconciliation are challenging to navigate, and survivor scars are jagged and deep. Just as my journey has morphed through the years into a search for understanding, love, and truth, it has become important for me to use my voice to build a world in which women and girls are free from violence in all its forms.

This is how my journey of healing began:

The silence was deafening. I couldn’t stop the roaring in my head, fierce pounding of my heart, and angry tears streaming down my cheeks. The silence was unbearable. I couldn’t breathe. I’d waited for this moment most of my life and now he’d robbed me with just three words.

“It. Didn’t. Happen.”

But it did, I remember. His warm breath against my neck, I was terrified when he climbed into my twin bed. His tongue sliding in my ear, whispering that I was a woman now. His coarse hands touching my breastless chest. His semen on my thigh. He slipped out from under my sunflower-covered sheets as silently as he crept in. In a panic, I darted across our bedroom and shook my younger sister until she awakened. We locked ourselves in the bathroom, twisting the old-fashioned key in the latch until it clicked. My tiny body shook while she ran bathwater. We climbed in together and I cried while she tried to wash away the stain of childhood sexual abuse. I was 10.

My father, Rev. James Luther Bevel, described in his Washington Post obituary as a “fiery top lieutenant of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and a force behind civil rights campaigns of the 1960s.” My father, a brilliant strategist who initiated some of the most important moments in our history – the Birmingham Children’s Crusade, the Chicago Open Housing Movement, and the first to call for a march from Selma to Montgomery to secure voting rights.

My father, who fought for my freedom before I was even born, molested me.

Early on, I refused my mother’s gentle suggestion that I speak with a therapist. Sitting silently as the psychologist impatiently checked her watch until the hour elapsed, I buried the dark pain deep in a place that protected and shielded me. For years, I shared with no one. Then, only a few trusted friends. Struggling internally, feeling alone, filled with overwhelming feelings of insecurity and inadequacy, oftentimes destructive and harmful to those I loved most, including myself. I, like so many others, cloaked and veiled my childhood sexual abuse in secrecy and shame.

When I first confronted my father about the incest, I was in my mid 20s, a young single mother of two sons, dedicated to thoughtful, intentional parenting. I was angry and filled with so much hatred towards him then. The abuse informed how I raised my sons in so many ways. When they were little boys, I was determined that they would be feminists, ever mindful that their male privilege demand they stand in solidarity with women and girls, I taught them the language of agency of their bodies. As they entered puberty, I shared sexual violence statistics and told them that many of the girls and women they would encounter throughout their lives would be victims and survivors. We delved deep in our “safe sex” talk. We explored the concept and importance of thoughtful partner intimacy. I shared my own experience with my father in an effort to build understanding and better contextualize for them how I came to be.

I received word my father would be in Memphis for a speaking engagement and called to ask him to meet with me on my terms, in a space that felt safe. When he said, “Yes” without hesitation, I imagined he must have known this day would eventually come. Consumed with hate, my heart heavy, I practiced what I’d been rehearsing in my head for years. I had even thought about the many excuses he’d make. And, how I’d destroy his feeble attempts to absolve himself.

My mother and younger brother came as support. My father sat stoically, legs crossed, on the living room floor, draped in black ministerial garb, wearing a colorful yarmulke. My sons were upstairs, occasionally letting out shrieks of laughter as they played, oblivious in their room.

My voice trembled with anger as 15-years of pain poured fourth. His abandonment as a parent – never providing even the “basics” – food, clothing, shelter. I grew up in abject poverty. Food stamp lines, government-issued powdered milk that never quite dissolved in lukewarm water, welfare worker visits, roaches in the refrigerator. My mom worked multiple low-wage jobs to keep a roof over our heads.

I yelled as I accused him of destroying my life. I stared into an all too familiar face. We share the same rounded nose, full lips, caramel colored skin, and rapid pace of speech. We share the same eyes, including the crease that begins at our inner corner and disappears into high cheekbones. WE WERE NOT THE SAME. I felt overwhelmed.

“You know nothing about me!” “Do you know the day I was born? Do you know my birth date? Do you??”

Unsure why that was suddenly so important.

“You never bandaged a knee, read a book, prepared a meal, sailed a kite, or listened to a piano recital! You weren’t there when I graduated high school or college or when your grandsons were born!” Sobbing, I screamed, “You’ve done NOTHING but rip open my soul!”

My father looked at me with deep intensity, sat silent for a moment, and then leaned close and in a calm, steady voice that I’ve not forgotten said,

“I got you the right to vote.”

When Ava DuVernay’s SELMA debuted last year, I was filled with pride and trepidation. In theatres across the nation, my father was being portrayed by Common, a conscious hip-hop artist and activist I’ve long admired.

I coordinated a citywide effort to view SELMA and honor six African American elected officials who were “firsts,” including our mayor who despite breaking some barriers refused to support a comprehensive Human Rights Ordinance in our city to expand protections for the LGBT community. I chose to highlight the intersection of these movements because that same week Florida celebrated marriage equality, the state in which I now live.

After the screening, more than a hundred of us engaged in intimate dialogue about the film, race relations, intersectional justice, and the current state of violence in our America. A powerful mosaic of our community grappling with many difficult questions and even fewer answers. A few folks alluded to the “controversy” surrounding my father’s incest “accusations.”

I am mindful that the Movement looms much larger than my father or his work, but I also know that there were men of the Movement who marginalized women and created space for various types of abuses, oftentimes not upholding the very principles upon which they stood. Some of the same men that viewed the accountability we demanded of our father as an assault on the Movement.

By the time he died of stage IV pancreatic cancer during the incest trial, I thought I had it all worked out. I’ve since discovered it’s a continuum. I’d not been angry with him for many years before the trial, but intense hurt and lingering questions hindered resolution. A few years ago, I saw “Mighty Times: The Children’s March” which tells the story of my father initiating and executing the Birmingham Children’s Crusade, and I couldn’t get through the award-winning documentary without crying. I rarely question the universe but that day, I did.

When I was a little girl, I often wondered how any human so filled with brilliance and love for humankind, so gifted by God, could be so flawed. Unsure of what emotions might arise watching SELMA, I was overcome with sadness each time his “face” appeared on screen.

Truth is complex. Yes, my father secured my right to vote and he also took away part of that freedom. I wonder if we both paid too high a price.

Filled with fury, I finally unleashed what I had only shared with a trusted few…

“You climbed into my bed. Your semen was on my thigh. I was a little girl. I am your daughter.”

Ready for anything he might say, I took a deep breath and stared into his eyes. He simply looked at me with a calm defiance for which I was unprepared and said.

“It. Didn’t. Happen.”

After my father’s funeral, a journalist asked if I loved him. Speechless because I had never pondered the question, I responded a few days later.

“I do love my father. I love him for the sacrifices he made that have enabled me to enjoy political freedom and social justice. I love him for his role in the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the vote I was able to cast that helped put a Black man in the White House.” It is also that love that gave me the strength to sit in a courtroom.

I sometimes think about the conversations we’ll never have. The intersection of our justice work on which we might have collaborated had he been willing to hold himself to truth. For me, the incest trial was never about vengeance or punitive justice. I wanted my father to be held accountable through the prism of love and truth, the community safe from sexual predators and healing…for my little girl self and my sisters.

My father is maybe not the monster I once believed him to be, more simply a man with human frailty, sexually abused as a child himself, trapped in a past from which he never healed, incapable of facing himself in the end. My life forever shaped in immeasurable ways by the fiery, best parts of him – the pieces of love, resilience, and brilliance that helped him shape a Movement. My life altered by his violation and strengthened by my resolve to reimagine love and legacy, and use the horror of my abuse in ways that are healing and empowering for me.

I am not nor will I ever be destined to live a legacy I despise. I have discovered that the complexity and constant evolution is real and worth exploring despite the pain.

I have chosen to use this experience and ongoing healing journey to stand for others who have yet to find their voice. This is #LoveWITHAccountability.

Chevara Orrin is a community catalyst, social entrepreneur, public speaker and justice activist in Jacksonville, Florida. Born the daughter of a white, Jewish mother and Black father, both human and civil rights activists, Chevara’s work in both the nonprofit, education and creative spheres has been shaped by her passion for equality, diversity and inclusion. In her current role as Chief Creative Catalyst for Collective Concepts, she is best known for having conceived and co-created We Are Straight Allies www.wearestraightallies.com, a national campaign to support LGBT equality and passage of comprehensive policies that protect the LGBT community. The award-winning campaign has drawn the participation of prominent figures such as feminist icon Gloria Steinem, Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, Olympic gold medalist and civil rights attorney Nancy Hogshead-Makar and nationally recognized corporate leaders. Chevara is also founder of #WhiteAndWokewww.whiteandwoke.org, a campaign designed to raise awareness among white people and create action to dismantle institutional racism and its corresponding white privilege.

Chevara’s professional portfolio includes more than 20 years of successful leadership in the arts and education. She serves on a wide range of community boards and has received numerous awards and recognition for her work. Chevara is also a cohort in the 2016-2017 Strategic Diversity Inclusion and Management Program at Georgetown University.

A survivor of childhood sexual abuse, Chevara is an outspoken advocate for the eradication of sexual violence against women and girls. In 2008, she founded WhiteSpace SafeSpace, a monthly support group and forum for incest survivors and is currently co-producing a documentary about her journey and breaking the cycle of abuse.